Too Big to Ignore: Why Goldman Can’t Afford to Get This Wrong

Gender discrimination is having a moment in the employment law world. An ongoing problem at all levels and in all types of employment positions, gender-based discrimination and harassment is omnipresent—but as 2016 comes to a close, it’s clear that heightened scrutiny on racial issues this year has given gender discrimination a multifaceted character, in turn leading to a well-deserved increase in attention from major firms and in public discourse. Surrounding the dialogue are three key questions: What happens when issues of race and gender intersect? How are employees and employers impacted? And what should we do about it?

In late October, Goldman Sachs’ Edith Cooper held an interview with LinkedIn to discuss the importance of promoting dialogue and difficult conversations surrounding race and gender in the workplace. The current global head of human capital management, Cooper has over twenty years of experience at Goldman, during which she’s gained significant insight about the dynamics of minority identities in the workplace—and particularly in the New York City investment banking world. She is a black woman, an executive vice president and partner at one of the most prominent companies on Wall Street, and, according to LinkedIn news editor Laura Lorenzetti Soper, is “part of the heart and soul of Goldman’s culture.”

Above all, Cooper is an institutional leader: when she speaks, her message “trickles down and well beyond the firm’s global offices.” She has a platform, as does Goldman—the gold standard on Wall Street. When Cooper talks, people listen; when Goldman acts, people follow. The firm sets pay scales, standards for equal pay, and precedents for corporate culture change. So the question is this: will Goldman’s promotion of “difficult conversations” around race and gender be enough? Or is there something more that corporations can—and should—be doing?

Perhaps one of the most problematic aspects of addressing race and gender issues in the workplace is that discrimination and harassment simply look different today than they used to. The recent HBO film “Confirmation,” released in April, reminded viewers of Anita Hill’s crusade against sexual harassment in the early 1990s with her testimony against Clarence Thomas—one of the key events that precipitated awareness of gender discrimination in the workplace. The term “sexual harassment” hadn’t even been coined prior to the 1970s, and traditionally, it had referred to blatant sexual advances on female employees, often under threat of retaliation. Hill’s testimony contributed to a broader understanding of harassment that included a pattern of behavior—a type of professional culture—that targeted women in the workplace, making them feel unsafe, unwelcome, or simply uncomfortable.

The allegations Hill brought against Thomas, whom she worked under in the 1980s, included claims that he had explicitly referenced sex and pornography in front of her and had repeatedly asked her out on dates despite her refusal. In front of an all-white, all-male panel of judges—and in front of viewers nationwide—the African-American Hill detailed a pattern of insidious, harassing behavior that was distinct from the more overtly physical instances of discriminatory conduct that had previously characterized sexual harassment. Even so, the examples that Hill gave in her testimony are still more blatant in character than many instances of sexual harassment today—if not the majority.

Over the past several decades, heightened public awareness and increased legal protections may have lessened (though not eliminated!) obvious instances of workplace harassment, but such measures don’t have the same effect against the more indirect culture of harassment that is prevalent in our modern day. As a result, many women don’t even recognize sexual harassment in the workplace for what is truly is—instead dismissing it, however uncomfortably, as just a part of daily life. The New York finance industry appears to be an especially proficient cultivator of this atmosphere: several prominent op-ed articles this year have drawn attention to Wall Street’s toxic “bro culture” and how it damages women.

It may seem counterintuitive that leading global investment firms like Goldman Sachs are apparently such significant contributors to the United States’ culture of workplace harassment—particularly considering that most Wall Street corporations require sensitivity training that addresses race- and gender-based discrimination. But again, insidious forms of harassment are so prevalent precisely because nobody wants to call them that. “Micro-aggressions,” small and seemingly innocuous instances of discrimination, are commonplace and can be easily excused—dismissed as comments made in ignorance or without ill intentions. Wall Street “bro culture” can certainly be micro-aggressive, but in its most devious form, micro-aggression involves generalized assumptions about an employee’s seniority, family life, professional experience, or expertise that are based on that employee’s personal attributes, such as race or gender (often both). Sometimes they’re simple mistakes based on misguided beliefs about certain demographics—and the consequent comments or behaviors aren’t legally actionable in the same way that more obvious harassment or discrimination is. Nevertheless, micro-aggressions in any form reflect the extent to which women and minority employees are considered subsidiary to the archetypal seasoned, white, male employee—particularly in professional corporate atmospheres.

In her September LinkedIn article, Edith Cooper recalled examples of micro-aggressions that she herself has experienced as a black female executive at Goldman Sachs—including being asked to serve coffee at a company meeting (she was there to run it) and how she gained admission to Harvard (she applied). “People frequently assumed I was the most junior person in the room, when in fact, I was the most senior,” Cooper wrote. “I constantly needed to share my credentials when nobody else had to share theirs. And, more often than not, I was the only black person—the only black woman—in the meeting.”

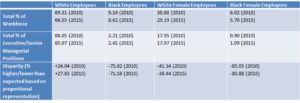

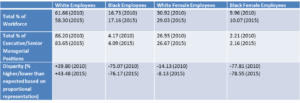

Cooper’s feelings of isolation are based in fact. Women and black employees in general are underrepresented in private industry—particularly so in finance. In executive positions like the one Cooper occupies, women and African-Americans are few and far between, and black women like herself are almost nowhere to be seen. Take New York State for example: last year in the private sector, 58% of all private industry employees were white, while 17% were black. But almost 84% of executive and senior managerial positions went to white employees, while just 4% went to black employees. The numbers are even starker when the statistics are reduced to New York’s finance and insurance industries: 85% of executives are white, and just 2.5% are black. In both cases, black female employees are consistently the most underrepresented demographic and face the greatest proportional disparity in total industry positions vs. executive positions. Shockingly, their representation in senior managerial positions is eighty-one percent lower than would be proportionally expected in New York’s finance and insurance sectors. The below data summarizes publicly available employment statistics from the EEOC:

New York State—All Private Industries

New York State —Private Finance and Insurance Industries

As these figures indicate, there is no clear upwards trend in New York employment patterns for women and minorities. The past five years have seen marginal increases in black employees’ representation in executive finance positions, but not in general across all private industries—representation has actually decreased. The disproportionately large allocation of white employees to senior managerial positions, meanwhile, has continued to increase in finance as well as in the general private sector.

Most importantly, while the disparity in black women’s representation in executive finance positions has improved slightly since 2010, the improvement is from 85% to about 81%—indicating that we still have a long way to go. Numbers are similar across the United States as a whole, but are decreasing instead, from 85.75% under-representation in 2010 to 86.58% under-representation last year.

Employment trends have a significant amount to do with race- and gender-based harassment in the workplace. Minority demographics’ limited presence at the top is a self-perpetuating negative cycle—if, as Edith Cooper’s career indicates, people don’t ever expect to see a black woman in a leadership role, how can we anticipate that these numbers will improve? Expectations are powerful. The culture of insidious discrimination that this under-representation promotes will continue to dissuade women of all races and national origins from joining (or remaining at) Wall Street corporations—and they’ll never even have the chance to rise to an executive level.

So to recap: the unfortunate truth is that discrimination of all types—even, and sometimes especially, at leading Wall Street corporations like Goldman Sachs—is both rampant and insidious. Even though our understanding of sexual harassment and discrimination has expanded over the past several decades since Anita Hill, it’s aching for another re-definition, as minor instances of discrimination and micro-aggressions continue to build and contribute to an unwelcoming atmosphere for women in the workplace—especially at high levels of employment. Statistics from just within the past five years show a disturbing under-representation of both white women and African-American women in the workplace, as well as in professional roles in the private sector.

Edith Cooper is a woman who’s personally experienced the detriments of being a black woman in a professional corporate atmosphere. Her informed solution, as an executive at Goldman, is to promote difficult conversations about race and gender and make employees “comfortable being uncomfortable.” She hopes that other companies “can learn from Goldman’s example and open up a dialogue with employees, even if it isn’t easy.” It’s not easy. That’s why dialogue has to be the first step—but it can’t be the only one. What else can Goldman do to set the standard for fair treatment of minority employees on Wall Street, other than talking about it? The world is watching. This is too big to ignore, and Goldman can’t afford to get it wrong.